Travel Tips

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Search

Early Islamic society, though initially tribal, evolved to embrace ethnic equality and meritocracy, enabling the mawali to make notable contributions in fields such as fiqh, hadith, and Arabic grammar. By the 4th century AD, non-Arabs comprised a majority of scholars, reflecting Islam's emphasis on knowledge over lineage. Despite not banning slavery, Islamic teachings encouraged the freeing of slaves, with many former slaves rising to positions of influence. The article highlights the pivotal role of mawali in shaping Islamic intellectual history, especially under the Abbasids

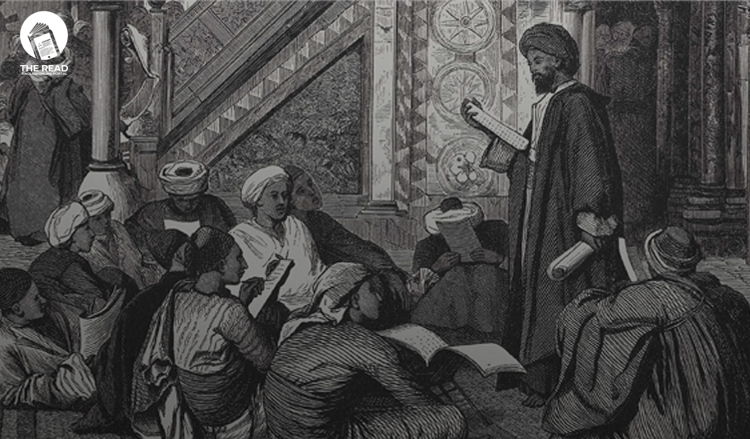

Early Islamic scholarship was not limited to Arabs; many scholars were non-Arabs and former slaves. This article highlights the significant contributions of the mawali, a term referring to freed slaves and non-Arabs, in Islamic intellectual history. The tribal system in the Arabian Peninsula led to the creation of the mawali category, which included many scholars who played a crucial role in stabilizing Islamic knowledge.

Islam’s call for ethnic equality adopted a meritocratic scholarly environment. Although some argue that non-Arabs outnumbered Arabs in scholarship, data shows a more balanced contribution: 51% Arab and 49% non-Arab scholars up to 400 AH/1010 CE. In the first century of Islam, Arabs made up 90% of scholars, but by the fourth century, non-Arabs set up 65%. Regional studies, such as those using Abu Ishaq al-Shirazi’s Tabaqat al Fuqaha, reveal varying ratios of Arab to non-Arab scholars across different areas.

Arabs were energetic to early Islamic scholarship, especially when most Muslims were Arab. Over time, non-Arabs turned to the majority. Despite the initial Arab numerousness, Islamic teachings emphasized goodness and knowledge over race or background, allowing diverse individuals to contribute significantly to Islamic scholarship.

HOW DID SLAVERY FUNCTION IN 7TH-CENTURY ARABIA?

Many people view slavery through the lens of American chattel slavery, which confuses discussions about slavery in the Islamic tradition. Unlike the ethnically based slavery in the Americas, slavery in 7th-century Arabia was not based on skin color or race. Slaves came from various backgrounds, with many being non-Arabs, and were integrated into their owners’ households. The Prophet Muhammad emphasized caring for slaves, urging that they should be clothed, fed, and treated as family. The Qur’an and Sunnah strongly encouraged freeing slaves, making it a requirement for forgiveness for certain sins.

In Islamic civilization, slaves were rarely enslaved for life and were often freed through various means, such as contracts of manumission, childbirth, or the owner’s declaration. The Qur’an’s appeal to free slaves led early Muslims to do so frequently, sometimes disregarding their wealth. For instance, the Prophet freed all the slaves gifted to him, showing his distaste for slavery. Although Islam did not prohibit slavery, it encouraged liberation, highlighting a significant distinction from other historical forms of slavery. This historical fact demonstrates that Islam, while not banning slavery, certainly did not promote it.

THE MAWALIS

In the 7th century, the Arabian Peninsula lacked formal government or states. Protection depended on family and tribal relationships rather than police or courts. Loyalty to one’s tribe was vital for survival, leading to the saying, “Support your brother whether he is oppressed or the oppressor.” Islam challenged this tribal system by encouraging justice and equality before God, as emphasized in the Qur’an. Vulnerable groups included women, orphans, and slaves, and the Prophet Muhammad’s call for justice was revolutionary.

Outsiders could be incorporated into the tribal system as mawali, a status also given to freed slaves. This system was crucial for transitioning from tribalism to Islamic rule. As Islam expanded, the term mawali was used more widely, including non-Arab converts. By the mid-Umayyad period, the tribal system had collapsed as an organizing tool, and later, Umayyad caliphs trusted the mawali for support.

By the 720s, Mawali had integrated into Arab society, speaking Arabic, intermarrying, and becoming prominent in business, scholarship, and culture. The Abbasid dynasty further eliminated policies distinguishing Arabs from Mawali, achieving social, educational, and economic equality. Scholars spoke against Arab superiority, and children of enslaved mothers redefined themselves as Arabs. Mastery of Arabic and Islamic scholarship helped Mawali gain political and religious positions. Eventually, ethnic distinctions faded, and Islamic culture became a shared identity, with Arabic as the language of courts and scholarship.

THE IMPACT OF MAWALI ON ISLAMIC SCHOLARLY ACHIEVEMENTS

Even during the time of the first four caliphs, Mawali (non-Arab converts and freed slaves) began playing significant roles in government and Islamic education. For instance, Caliph Umar once questioned why a mawla, Ibn Abza, was left in charge of Mecca during Hajj. The response highlighted Ibn Abza’s knowledge of the Qur’an and obligations, to which Umar acknowledged the Prophet’s statement that God will uplift some and lower some through this religion.

The influence of Mawali increased under the Umayyads. Scholar Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri reported to Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan that many religious leaders in various regions were mawali. This made the caliph wrong about the future of the Arab community. However, al Zuhri reassured him that religious leadership depended on those who preserved Islam. Mawali led most major learning centers by then, illustrating a significant shift in the Muslim empire. Under the Abbasids, the role of non-Arabs flourished. Mawali became a considerable part of the scholarly and political class. Al Zuhri and Ibn Khaldun noted that non-Arabs carried much of Islamic knowledge.

Non-Arabs compiled the six major Sunni hadith collections, and nearly half of the narrators in these collections were Mawali. This shows that being a former slave or non-Arab did not delay one from preserving the Sunnah. Many Mawali came from literate backgrounds and stepped up to play leading roles in forming Islamic sciences after the Companions’ era. They contributed significantly to Fiqh, hadith, tafsir, and Arabic grammar. Islamic scholarship owes much to the contributions of non-Arabs and former slaves, thanks to Islam’s emphasis on equality, allowing everyone to contribute regardless of race or social status.

Comments